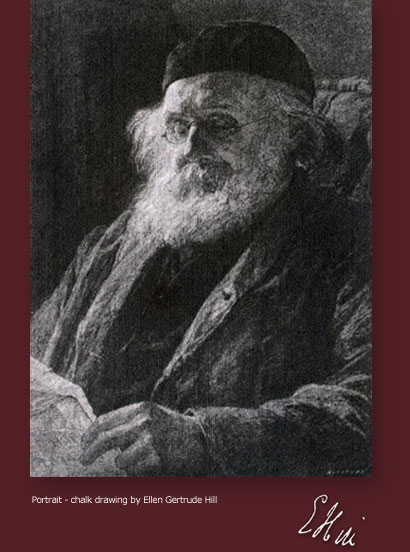

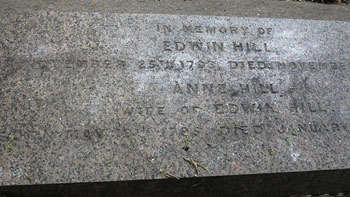

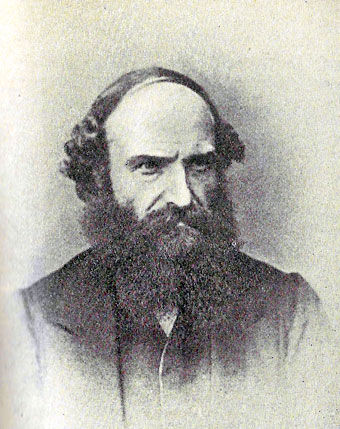

Edwin Hill (1793 - 1876)

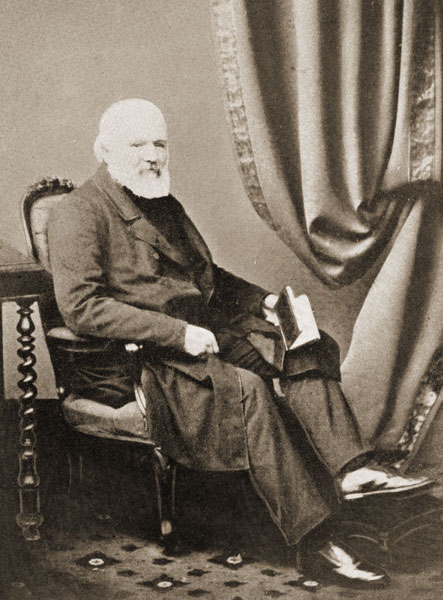

Edwin Hill (1793–1876), civil servant and inventor of postal machinery, was born on 25 November 1793 at Birmingham, son of Thomas Wright Hill (1763–1851) and his wife, Sarah Lea (1765–1842). His younger brother was postal reformer Rowland Hill.

Life

Edwin Hill was born in Birmingham as the second of eight children. He was educated at Hazelwood School, run by his father, where he also taught when older and a branch of the school was founded at Tottenham. Later he worked at the Assay Office in Birmingham and then at a Birmingham brass-rolling mill where he became the manager.

In 1819 he and his brother Matthew married sisters, respectively Anne (1795–1882) and Margaret Bucknall. Edwin and Anne had ten children, seven of whom survived him. Amongst them were: Albert, Ormond, Katherine, Julian, Bertha Mary, Marcia Elizabeth, Olivia Margaret, Franklin and Louisa Hill.

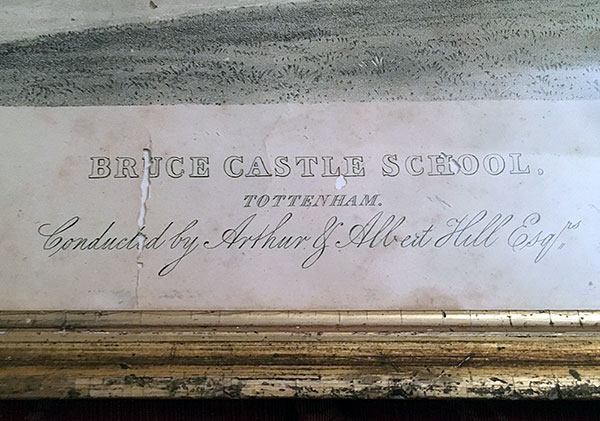

In 1827, when the family school extended to Bruce Castle, Tottenham, in addition to the existing establishment at Hazelwood, Birmingham, Edwin Hill joined the enterprise and moved to Tottenham where Rowland took charge of the teaching. Edwin was mostly concerned with the commercial management, being too much interested in his mechanical experiments to give up much of his time to teaching.

Hill was an inveterate inventor of equipment to help the stamp department for the postal reform by his brother Rowland.. On his retirement a Treasury minute praised Hill's "...resourcefulness and considerable mechanical ability which had contributed so much to the success of the new postage scheme".

In 1840 Hill became the British Controller of Stamps and he remained in that position until 1872.

Hill campaigned for legal and political change. He was one of the signatories to the notice calling a meeting on 22 January 1817 to petition for parliamentary reform and he campaigned for changes to the law relating to the handling of stolen property.

Furthermore he was concerned with the principles of currency.

Edwin Hill died on 6 November 1876 at his home, 1 St Mark's Square, close to the entrance to the London Zoo. He is buried at Highgate Cemetery (Grave no. 4149 square 27 Western Cemetery).

The Hill Brothers

Thomas Wright Hill had eight children: Matthew Davenport, Edwin, Rowland, Arthur, Caroline, Frederic, William Howard and Sarah Symonds Hill. Whereas William and Sarah died quite young, Caroline (born 1800) emigrated to South Australia with her husband Francis Clark in 1850 for health reasons.

The brothers Matthew, Edwin, Rowland, Arthur and Frederic worked close together with their father on several social and political reforms. Their thinking might be described as never respecting the status quo, always asking how things could be made differently and more beneficially for mankind.

The School

At Bruce Castle, Tottenham, in 1819, they founded a branch of a school, which Thomas Wright Hill had started at Birmingham (The Hazelwood School System). The school was run along radical lines inspired by Hill's friends Thomas Paine, Richard Price and Joseph Priestley. All teaching was on the principle that the role of the teacher is to instill the desire to learn, not to impart facts, corporal punishment was abolished and alleged transgressions were tried by a court of pupils, while the school taught a radical (for the time) curriculum including foreign languages, science and engineering.

Bruce Castle, Tottenham, London, 2014 - © Christoph Oertel

Rowland Hill, who had written an influential proposal on postal reform, was appointed to bring on the reform, where he introduced the world's first postage stamps, leaving the school in the hands of his younger brother Arthur Hill, who retired in 1868, leaving the school in the hands of his son Birkbeck Hill and Edwin's son Albert Hill.

Original drawing Bruce Castle School © Christoph Oertel

Detail on bottom: Bruce Castle School - Conducted by Arthur & Albert Hill Esq.

Albert Hill

The Postal Reform

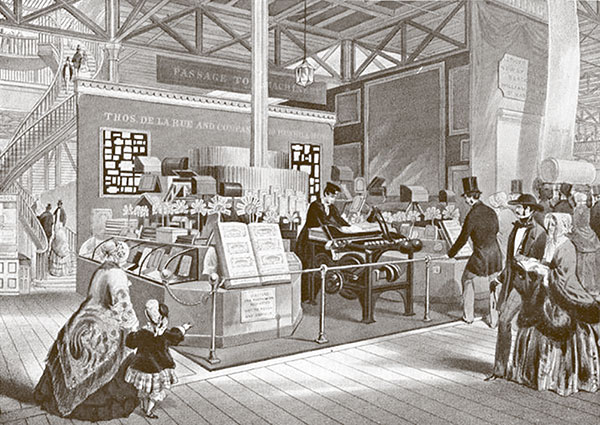

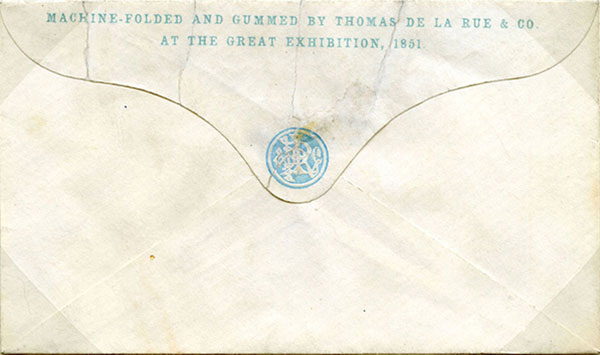

Edwin Hill helped his brother Rowland by inventing and bulding the first letter scale and a mechanical system to fold and gumm envelopes, which was shown at the Great Exhibition of 1851 in London, the patent for which was bought by Warren de la Rue to whom the machine was attributed.

The envelope machine shown at the Great Exhibiton 1851, London, at the booth of De la Rue

(picture from www.victorianweb.org)

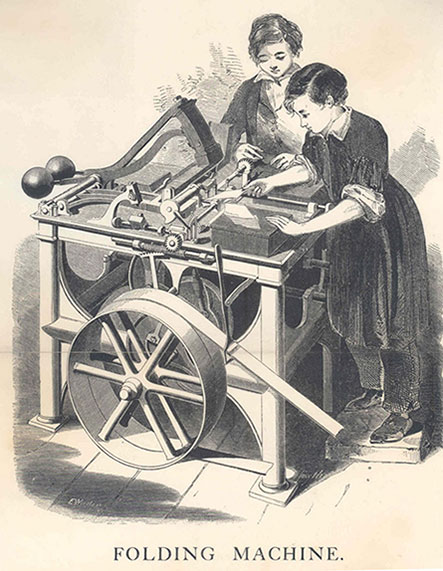

The envelope folding machine at the Great Exhibiton 1851

(picture from www.postalmuseum.org)

An original envelope folded by Edwin's machine at the Great Exhibiton, 1851

(picture from www.postalmuseum.org)

In 1840, with penny postage about to commence, it was necessary to expand the stamp office. Stamps had long existed as a tax-collecting device, but now the Inland Revenue was to supply the Post Office with the new postage stamps. Rowland was appointed to the Treasury to oversee the introduction of the system, and Edwin applied for the stamp-producing appointment. Here he remained, joined later by his son Ormond, until his retirement in 1872.

Ormond Hill

Quotes from the book:

"Frederic Hill: An Autobiography of Fifty Years in Times of Reform"

In the book, Constance Hill, the daughter of Frederic, remembers tellings of her father about his brother Edwin:

"For thirty years his brother Edwin held the office of Comptroller of the Stamp Department at Somerset House, where his mechanical talents came into play. His many contrivances are amusingly described in the Daily News of November 3, 1871:

"Once fairly underground, and it is as if we were in the cave of an amiable magician. Doors open of their own accord.; stamps of fabulous value are created out of waste-paper by a wave of the hand; wooden arms and limbs are moved by unseen agencies and classify documents with inconceivable rapidity and unfailing exactitude. Bundles of valuable deeds . . . walk gravely into the room unaided, and present themselves silently to be stamped. Other mysterious contrivances for lessening human labour abound . . . ingenious inventions of the Comptroller of the Stamping Department."

"My uncle's bedroom was a museum of curiosities, affording much amusement to all who were allowed to inspect it. A network of cords stretched across the bed-head and ceiling. If at night the blankets pressed upon him too heavily, he could, as he lay, pull a string, with a sort of claw at the end, which grasped the bedclothes and relieved him of their weight. Again, if he awoke early and wanted to know the time, he could pull a cord which opened the shutter to admit the light, and by pulling another cord he could shut it again, and so on !"

"My uncle Edwin had a most kind heart, as may be guessed from his care for the rheumatic porter. He carried his sympathy for pain or discomfort to an extreme point. When his children were young, and complained of a tight frock or an uneasy shoe, out came his penknife to remedy matters by a good slit! He was as simple as "Dominie Sampson" with regard to his own clothes, and his wife managed their renewal in much the same way as that recorded in the case of the "Dominie." When her husband's black velvet waistcoat, or any other garment, was getting shabby, she took it away overnight and put a new one in its place, the metamorphosis remaining alike undiscovered !"

"One hot summer day my uncle Edwin was walking in Kensington Gardens, absorbed in argument, with his brothers Rowland and Frederic. A gardener happened to set down a pail of water within his reach. To cool his feet he put first one leg into it and then the other, gesticulating and arguing all the time, while the gardener stared in amazement !"

"He was especially fond of arguing upon his favourite subject, which his old friend Mr. Kerr of Glasgow called "that infernal currency" but his mind turned also to a very different enjoyment. The same friend said of him that "he was astonished at the correctness of his memory in quoting passage after passage of poetry, and at the almost girl-like ardour with which he recited them." (Constance Hill)

Frederic Hill remembers:

"The subject of currency first interested us during this period [1832-1835]. My brother Edwin and I entered into a series of discussions upon it with each other. We invited Rowland to join us, but he had too many other matters in hand to be able to do so. Edwin and I both gradually formed opinions which remained unchanged in after-life, and which we have advocated as occasion offered. One of these was in favour of a paper currency. Many years later Edwin published his work upon the "Principles of Currency, Means of securing Uniformity of Value and Adequacy of Supply."

"In the year 1832 we established what we called the "Family Fund." Its object was to secure every member of our family (five of whom were now married) from pecuniary anxiety. The necessary expenditure of each branch of the family was assessed, and half the remaining surplus income, in each case, was handed over annually to the "Family Fund." Its management, together with the selection of investments, was entrusted to me.

This fund continued in being for twenty-four years; at the end of which time the general condition of our family had so far improved that all pecuniary anxieties had disappeared. The balance, which had much increased in amount, was then divided; each person's share being in proportion to his original contribution."

Further readings:

- Hill, Edwin: "Principles of Currency, Means of securing Uniformity of Value and Adequacy of Supply", London, 1856

- Hill, Rowland and Hill, George Birkbeck: "The Life of Sir Rowland Hill and the History of Penny Postage", London, 1880

- Hill, Frederic: "An Autobiography of Fifty Years in Times of Reform", edited by his daughter Constance Hill, London, 1894

- Hill, W.E.: An account of the Julian Hill family. London, 1938. (privately printed)

- Hill, I.D., "Hill, Edwin (1793–1876)", Oxford Dictionary of National Biography, Oxford University Press, Sept 2004; online edn, Jan 2008. Retrieved 13 October 2009.

- Hey, Colin G.: "Hill, Rowland: Victorian Genius and Benefactor"

Many books have been republished and are available online.

My name is Christoph Oertel and I'm a descendant of Edwin Hill.

In deep love I dedicate this memorial page to my dear great x3 grandfather Edwin.

There is a huge family tree including many members of the Hill famiiy online

(ask the webmaster for a password if interested).

If you have any questions or suggestions please contact the

.